More oil and gas isn't a sustainable route to UK energy security

- May 12, 2022

- 4 min read

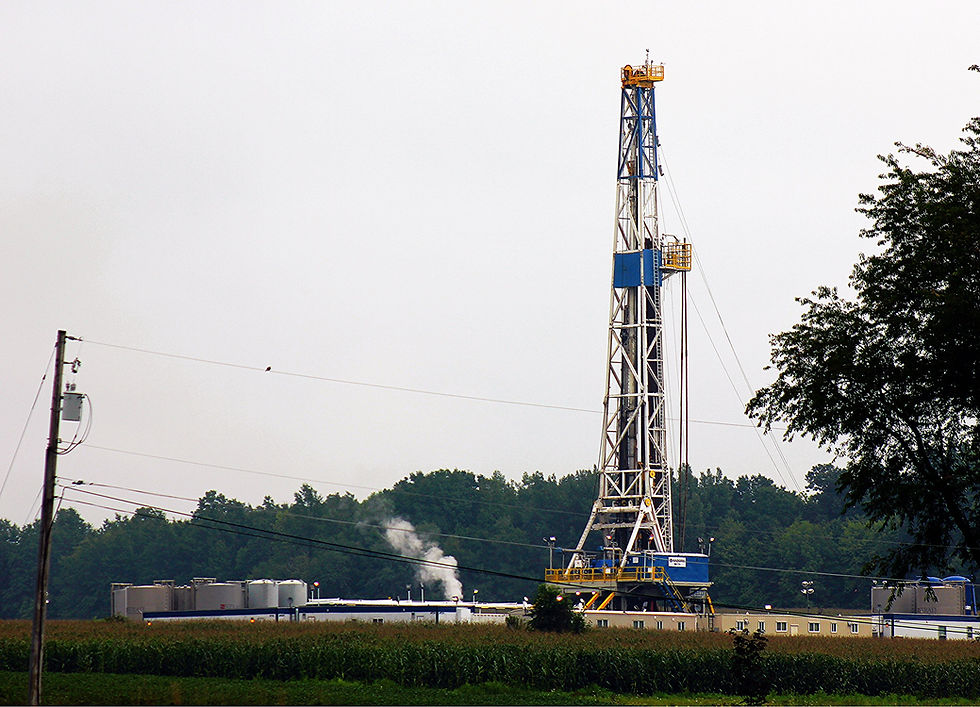

Rising energy bills and the Just Stop Oil protests have reignited the debate about UK oil and gas production. The centre-right has long been sceptical of calls to ‘keep it in the ground’, given the ongoing – albeit shrinking – need for oil and gas in our economy.

The drive to wean Britain and the rest of Europe off Russian hydrocarbons has brought the security case for domestic oil and gas production into sharper focus. Some are also calling for the UK to get drilling as a supply-side measure to ease pressure on energy bills, despite the fact our gas market is connected to Europe’s.

Very few supporters of climate action would argue against sweating existing North Sea oil and gas assets or issuing permits to oil and gas fields that can start producing in the next couple of years. This would clearly make a positive contribution to domestic energy security, even if it would not materially lower prices.

However, the energy security and affordability case for new oil and gas exploration is harder to sustain, given the length of time for these projects to start producing oil and gas – the Climate Change Committee cites an average of 28 years from the licence being granted to production.

The Energy Security Strategy published last month committed to a new wave of exploration licences this autumn. But in a rush to pump more oil and gas out of the North Sea, we must not lose sight of several key facts.

The first is that renewables are now outcompeting fossil fuels. Before the current gas price spike, renewable power was cheaper than fossil fuels in 90% of the world. The invasion of Ukraine has pushed up gas prices further and accelerated this trend, bringing forward the date when clean technologies reach cost parity with fossil-fuel equivalents.

Rapid cost reductions for green hydrogen – made from water and renewable energy – may surpass expectations too. Green hydrogen will be a critical clean fuel, helping decarbonise industry and certain types of transport and balancing a power grid dominated by variable wind and solar. It is competing against ‘blue hydrogen’ – produced from gas with carbon capture technology – for the clean hydrogen market.

If green hydrogen becomes cost-competitive with blue hydrogen much sooner than the 2030s, as experts previously forecast, this will reduce demand for one of the largest projected future uses of gas. Once this and other price tipping points are reached, the market for oil and gas will contract quickly.

Of course, even if demand is set to fall faster than expected, it doesn’t mean we won’t need fossil fuels for decades to come. Some will argue that it’s better to meet that demand, however fast it is shrinking, with UK supply.

This brings us to the second key point: the North Sea is a mature basin, meaning it is increasingly expensive to extract oil and gas from its remaining reserves. Even though currently high oil and gas prices are making some previously marginal projects in the North Sea economically viable, prices won’t stay this high forever, and investors know this.

It would also be politically extremely challenging to offer even more generous tax reliefs to our oil and gas companies, when they are currently making windfall profits and voters are seeing their energy and fuel bills rocket. What’s more, there are already generous tax reliefs in place, which have seen some oil and gas companies pay very little corporation tax in recent years.

This leads to the third key fact: if North Sea fossil fuel extraction ceases to be economical, energy firms might not realise the value of new exploration projects. Investors and regulators increasingly view further UK oil and gas exploration as a financial risk. Arguably this is a risk that energy firms should be free to take, but bad investments could lower the value of people’s pensions and harm the health of our financial sector more broadly.

The Government is introducing a mechanism to limit the risk of oil and gas ‘stranded assets’ – a climate compatibility checkpoint for new exploration licences. There are several potential checkpoint definitions, and the details are still to be finalised, but it is an essential policy if we’re to mitigate against stranded assets. The checkpoint must make sure production falls in line with projected domestic demand to be effective.

While we need a secure supply of fossil fuels for as long as there is demand, we must be wary of encouraging excessive investment in fossil fuels when the market is moving in another direction. Putin’s war and influence over energy markets have only spurred pre-existing trends toward greener energy. Opening many new oil and gas fields that will likely be uneconomic before they start operating will not contribute to energy security or affordability.

Instead, the Government should prioritise clean energy deployment, combined with further energy efficiency improvements and electrification of as much of the economy as possible, to bring about a clean, secure, low-cost energy system. This will be better for jobs and the balance of payments in the long run, too.

First published by CapX. Sam Hall is the Director of the Conservative Environment Network.

Comments